Years of Decline: Mismanagement and the Slide Toward 2011

In the late 2000s, Club Atlético River Plate – one of Argentina’s most successful football clubs – began a precipitous decline that few could have imagined. The trouble started at the top. Under club president José María Aguilar (2001–2009), River fell into financial disarray and institutional chaos. By the end of Aguilar’s tenure, the club had amassed a debt of roughly 140 million dollars, and desperation moves in the transfer market became common. Dozens of players were signed and sold, but on the pitch River’s fortunes waned. In 2008, just months after winning the Clausura championship, River finished last in the Apertura – the first bottom-place finish in club history. The shock of seeing Los Millonarios at the foot of the table was a harbinger of worse to come.

Aguilar’s mismanagement left River in a vulnerable state. In December 2009, legendary former player Daniel Passarella won the presidency, inheriting a club mired in debt and distress. Passarella would later claim he found “sponsorship contracts paid out in advance and the club only owning fractions of players’ transfer rights,” with virtually no funds to sign reinforcements. The first team was forced to rely on untested youth players and loanees. Meanwhile, results on the field remained middling at best.

Argentina’s peculiar relegation system (based on a three-year points average), the poor campaigns planted a ticking time bomb under River. Even as the team’s form improved slightly in 2010–11 under coach Juan José López, the accumulated average was perilously low. Simply put, the giant was standing on the thinnest of trapdoors.

Off the field, tensions mounted. The famously demanding River supporters grew restless after years without a major trophy (the last league title had come in 2008) and the unthinkable prospect of relegation crept into conversations. Internally, the Passarella administration struggled to contain crises. Players went unpaid for months, and the president butted heads with Julio Grondona, the powerful AFA chief, potentially isolating River from political goodwill when it was most needed. All of these factors converged in mid-2011, setting the stage for a historic fall. For a club that had amassed 33 league titles – more than any other in Argentina – and never left the top division in 110 years, the looming specter of relegation felt surreal. Yet, by June 2011, that specter was painfully real.

The Unthinkable: River Plate Relegated in 2011

On June 26, 2011, the unthinkable happened: River Plate, one of the nation’s cinco grandes, was relegated from the Primera División for the first time in its history. The decisive blow came in a two-legged relegation playoff (Promoción) against Belgrano de Córdoba – a modest provincial club cast as David to River’s Goliath. In the first leg on June 22 in Córdoba, River fell 0–2, a night marred by chaos as a group of furious River ultras (barrabravas) invaded the pitch to confront their own players face-to-face.

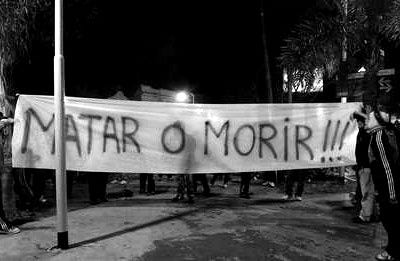

One ominous banner appeared outside River’s training ground before the return leg, encapsulating the desperation: “Matar o morir” – “Kill or die”. The message was clear: survival in the top flight was an absolute imperative.

Four days later, a tension-choked Estadio Monumental in Buenos Aires hosted the second leg. More than 70,000 anxious fans packed the stands. For a brief moment, hope flickered. At the 6-minute mark, striker Mariano Pavone ignited the stadium with a thunderous goal from outside the box to put River ahead 1-0. River now trailed by just one goal on aggregate, and belief surged that the nightmare might yet be averted. “¡Vamos todavía!” roared the commentators as the crowd’s roar shook the concrete bowl of the Monumental.

But as the minutes wore on, the weight of history grew heavier. Needing one more goal to erase the first-leg deficit, River grew anxious and Belgrano grew bold. In the 62nd minute, a defensive lapse by River opened the door for Belgrano’s Guillermo Farré, who pounced and scored to make it 1-1. A stunned silence fell over Núñez – River again needed two goals, with time slipping away. Then, at the 69-minute mark, lifeline: referee Sergio Pezzotta awarded River a penalty kick. Pavone, the hero of earlier, stepped up to take it – this was salvation on the spot. He struck low and hard… but poorly. Belgrano’s goalkeeper Juan Carlos Olave guessed right and smothered the weak attempt. Despair engulfed the Monumental. Olave instantly became a Cordobés hero, while River’s hopes crumbled. “Era la última pizca de esperanza” – the last pinch of hope – and it had slipped away.

By the final minutes, with River still trailing 1-3 on aggregate, emotions in the stands swung from anguish to fury. A contingent of enraged fans could contain themselves no longer. They began hurling objects onto the field, tearing up seats and even setting sections of the stands on fireIn the 89th minute, before the referee could even whistle full time, the match was stopped as the chaos spiraled out of control. A ring of security encircled the players at midfield while riot police moved in. The scene was apocalyptic: clouds of smoke and tear gas wafted over the pitch, helicopters buzzed overhead, and the wail of sirens mingled with the angry screams of rioting supporters. “Las postales son devastadoras,” noted La Nación – the images were devastating. Grown men in River jerseys stood sobbing inconsolably on the terraces; on the field, River players in disbelief wept openly as they were hustled away under police protection. In the concrete corridors beneath the stands, vandals vented their rage by smashing facilities; outside in the surrounding streets of the Barrio Núñez, running battles erupted between hooligans and riot police. The “Monumental War,” as some newspapers dubbed it, left a trail of destruction. Authorities later reported around 50 arrests and roughly 70 injured, including dozens of police officers, in the post-match violence. Two officers were hospitalized with serious head injuries from projectile strikes.

When the dust settled, the unimaginable had become reality: River Plate, 110 years in the top division, was now a second-tier team. “Lo imposible, para muchos, se volvió realidad,” wrote TyC Sports – the impossible had become real. The autopsy of a footballing giant’s downfall began immediately in media studios and on street corners. Many labeled this the darkest day in River’s history, and indeed it was. Fans and pundits cast about for culprits: blame fell on coach Juan José López for late-season “erratic team selection and conservative tactics,” on generations of underperforming players, and overwhelmingly on the club’s directors. Passarella, the president, and Aguilar before him were singled out by the masses as architects of the disaster. Under heavy pressure, Passarella refused to resign – “Me van a tener que sacar con los pies para adelante,” he defiantly said (“They’ll have to carry me out feet-first”). It was a bold statement from a man many held responsible, but in truth the failures had been years in the making. As one analysis noted, “River’s relegation is far more complex than a single season’s poor form”. The points-average system meant the sins of 2008–2010 had come back to haunt them. Still, none of that tempering context lessened the shock. River Plate’s fall sent shockwaves through Argentine fútbol and made headlines worldwide. If a club this large could collapse, what did it mean for the traditional powers of the sport? For River’s millions of fans, it meant an unfathomable grief – a mix of anger, shame, and sadness – but also, as events would show, the start of an unexpected rebirth.

Exile and Rebirth: The 2011–12 Season in Primera B Nacional

River Plate’s first (and only) season in the second division – the Primera B Nacional 2011/12 – was a journey of humility, soul-searching, and ultimately redemption. The reconstruction began almost immediately after the relegation playoff. In the locker room rubble of that June 26, 2011 defeat, as tearful players grappled with the reality of the drop, one emblematic striker, Fernando Cavenaghi, picked up his phone. Cavenaghi, a beloved River youth product who had been playing abroad, called the club and volunteered to return home at once, swearing to help River “en la que sea” (in whatever division). He wasn’t alone. The very next day, captain Matías Almeyda, who had been one of the few experienced leaders on the pitch during the Belgrano debacle, announced his retirement as a player and accepted the unenviable task of managing River’s campaign in the second tier. It was a stunning transition – from playing midfield one day to being presented as head coach the next – but Almeyda’s willingness to “carry the backpack” of responsibility spoke volumes about his love for the club.

In those dark hours, gestures like Cavenaghi’s and Almeyda’s offered flickers of hope. The fan base, too, underwent a profound transformation. River’s supporters, famous for their high expectations (the so-called paladar negro that demands stylish, attacking football), now rallied in unconditional solidarity. Chastened by catastrophe, fans pledged to stand by the team “en las malas mucho más” – even more so in bad times. Suddenly, the often half-full Monumental was packed to capacity for B Nacional games, and thousands of River die-hards caravanned to dusty provincial stadiums to cheer on their fallen giants. As one observer noted, the relegation removed a “thorn” from the fan’s pride – it became a mission to prove their loyalty and help River back to where it belonged. The atmosphere at second-division matches was electric; River’s games drew first-division-sized crowds and intense media coverage, turning the B Nacional into a de facto extension of the top flight for that year.

Reinforcements arrived to buttress the promotion bid. In January 2012, midway through the season, midfielder Leonardo Ponzio chose to leave Spain’s Real Zaragoza – forfeiting top-division football in Europe – to return to River, the club where he had played a few years prior. Around the same time, a high-profile champion joined the cause: David Trezeguet, a World Cup winner with France in 1998 and lifelong River fan, signed on to fulfill a boyhood dream of wearing the red sash – even if it meant doing so in Argentina’s second division. These moves were signals of change: important figures were willing to sacrifice and embrace the challenge, suggesting that River’s institutional pride was reawakening.

Still, the campaign was anything but a carefree romp. Every lower-league opponent treated matches against River like their cup final, and the pressure on Los Millonarios to win week in, week out was immense. The Primera B Nacional season stretched 38 games, a grueling tour of duty in unfamiliar territory. River stumbled at times – they suffered shock losses to clubs like Atlético Tucumán, Aldosivi, and even a humbling 0–1 defeat to Boca Unidos (a second-division namesake of their archrivals). As the season entered its final stretch in early 2012, the race for promotion tightened. By the penultimate round, River had alarmingly lost 0–1 to Patronato in Santa Fe, putting their top-two position (and automatic promotion) in jeopardy. Nervous flashbacks to the prior year’s collapse began to surface among fans and media. However, River’s closest challengers – Instituto de Córdoba and Rosario Central – failed to capitalize on River’s slip, setting up a nail-biting final day showdown.

That final day, June 23, 2012, will forever be etched in River Plate lore as the day of “La Resurrección.” In a sweltering Monumental stadium – exactly 363 days after the relegation – River faced Almirante Brown needing a win to secure promotion. The nerves were palpable; one reporter described the Monumental that afternoon as “immersed in a capsule of nerves and drama”. Fittingly, it was David Trezeguet, the veteran who had returned for this very moment, who rose to the occasion. Early in the second half, Trezeguet was involved in a scrappy sequence where a borderline offside header bounced to Rogelio Funes Mori, who fed the ball back to Trezeguet – the French-Argentine lashed a glorious strike into the net. The Monumental erupted in cathartic joy as River went 1-0 up. Later, in the 89th minute – after Trezeguet had even missed a penalty in between – the striker sealed the 2-0 victory with a second goal, finishing a counterattack to spark delirium. The final whistle confirmed it: River Plate were champions of Primera B Nacional and were heading straight back to the Primera División after one torturous year away. El Monumental was a volcano of relief and celebration. Players and fans alike were overcome with emotion – there were tears of joy this time, and renditions of the club anthem ringing out into the winter sky. The squad donned special commemorative T-shirts that read “23 J (June) – La Resurrección”, marking the date that the “resurrection” was complete. As one headline put it, “El final de la pesadilla” – the nightmare was over. River had clawed its way back.

The numbers from that season tell a story of eventual dominance: River finished first with 73 points (20 wins, 13 draws, 5 losses), edging Quilmes by a single point in the table. But beyond the stats, the experience fundamentally changed the club. The humiliation of relegation galvanized a new mentality: humility, unity, and an appreciation for the basics of fighting for results. As River legend Enzo Francescoli would later reflect, “Cuando uno toca fondo y empieza de cero, hay que arrancar… por suerte River empezó bien.” (“When you hit rock bottom and start from zero, you have to start again… luckily River started off on the right foot”). The club had been cleansed in a sense – its fanbase re-energized and its mission refocused. Still, as River rejoined the top division in August 2012, it faced a crucial question: How to ensure that such a calamity never happened again?

Rebuilding the Giant: 2012–2014

Back in the Primera División, River Plate entered a period of rebuilding and soul-searching. The mandate was clear: restore the club to its former glory and repay the faith of the fans who had endured the bitter journey through the “B”. The initial returns in late 2012 were mixed. Under coach Matías Almeyda, the team’s form in the 2012–13 season was erratic, hovering around mid-table. The lingering hangover of relegation was evident – confidence was fragile and the specter of the promedio (relegation averages) still loomed until River could rack up enough points. By November 2012, with the team’s results unconvincing and the Monumental demanding more, a change was made. Almeyda was let go, and River turned to a familiar face and fan favorite: Ramón Díaz.

Ramón Díaz – the club’s most successful coach of the 1990s (and architect of the 1996 Copa Libertadores win) – returned for a second stint at the helm, ushering in hope that River’s renaissance would accelerate. Under Ramón, River began to recover its competitive edge domestically. In the 2013 Torneo Final (the closing half of the season), River finished as runners-up, a significant improvement that signaled the club was becoming a force again. In early 2014 came a symbolic milestone: in March, River won a Superclásico 2-1 at Boca Juniors’ La Bombonera, their first away victory over Boca in a decade. The long wait to taste triumph on enemy soil was over, and it felt like another curse lifted. Ramón’s work culminated in May 2014, when River clinched the Torneo Final 2014 championship, securing the club’s first Primera División title since 2008After the trauma of relegation, River were kings of Argentine football once more. The title prompted an outpouring of joy among Los Millonarios faithful – a vindication that the club’s identity was intact and its winning ways restored.

Surprisingly, just days after winning that 2014 title, Ramón Díaz announced his resignation. Citing personal reasons and perhaps sensing that his mission was complete, the idolized coach stepped aside on a high note, leaving many supporters stunnedl. His departure coincided with major changes in River’s front office. In December 2013, a new president, Rodolfo D’Onofrio, had been elected, and he appointed club legend Enzo Francescoli as technical director (sports manager)r. Together, D’Onofrio and Francescoli were charting a modern, long-term project for River. Now they faced a pivotal decision: choosing Ramón’s successor to lead the team forward.

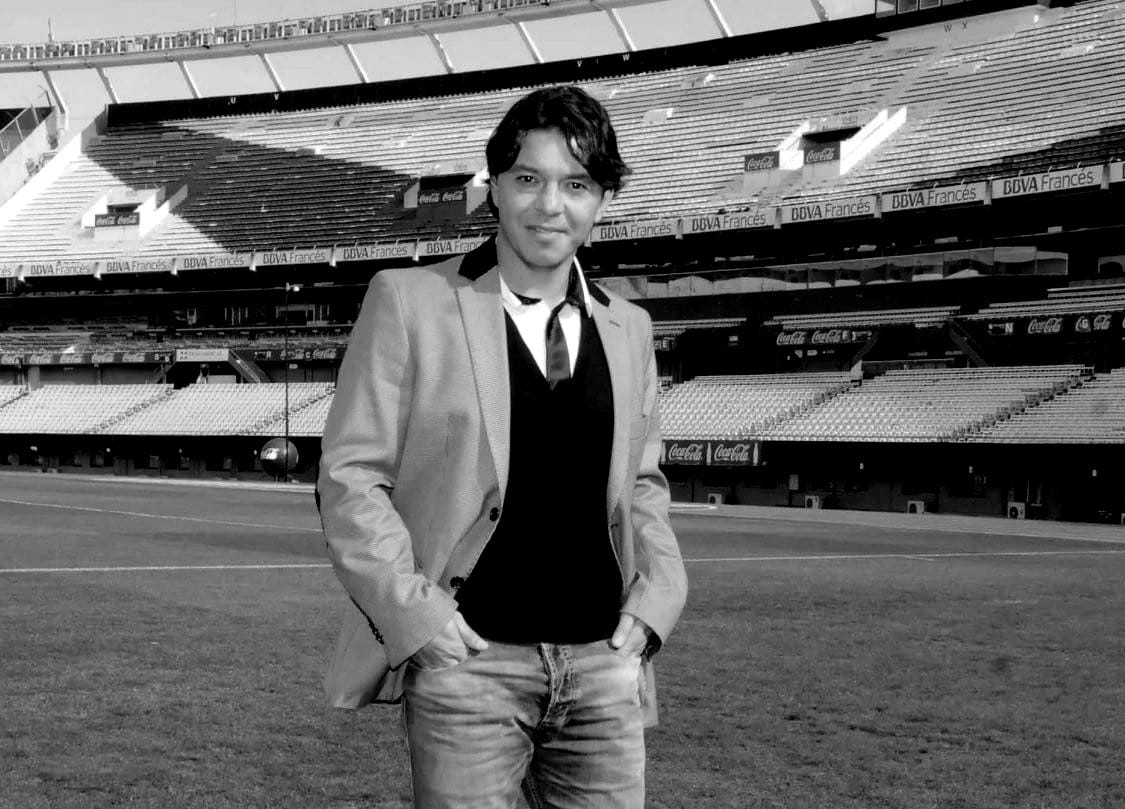

In June 2014, Francescoli made what proved to be a visionary choice: he recommended a relatively young, unproven coach named Marcelo Gallardo. Gallardo, a former River playmaker nicknamed “El Muñeco” (“the doll”) for his boyish looks as a player, had only a brief coaching stint at Uruguay’s Nacional on his résumé. Yet he was a student of the game, a club idol from his playing days, and someone who understood River’s demanding culture. With Francescoli’s backing, Gallardo was handed the reins. Thus began one of the most extraordinary managerial tenures in South American football history – a period that would erase any remaining scars of 2011 and elevate River Plate to unprecedented heights.

The Gallardo Era: From Redemption to Dynasty (2014–2021)

Marcelo Gallardo took charge in mid-2014, and what followed was a golden era that transformed River Plate’s narrative from redemption to dominance. If the years immediately after relegation were about righting the ship domestically, Gallardo’s reign would steer that ship into uncharted waters of international glory. Success came swiftly. In the latter half of 2014, Gallardo’s dynamic, fearless style rejuvenated River. The team went on a 31-match unbeaten run across competitions, playing with a blend of grit and attacking verve that thrilled fans. The ultimate reward came in December 2014, when River won the Copa Sudamericana, South America’s secondary continental tournament. In that campaign, River vanquished none other than archrivals Boca Juniors in a dramatic semifinal (winning 1-0 on aggregate in a tense, no-away-goals affair), exorcising ghosts of past international meetings with Boca. They then defeated Atlético Nacional of Colombia in the final to claim River’s first international trophy in 17 years. As ESPN aptly put it at the time, “Three years ago, River were battling back from relegation... Now they have regained their footballing identity and added silver to the trophy cabinet”. Indeed, the Sudamericana title in 2014 was proof that River was back among the continent’s elite.

The momentum carried into 2015. In early February, River beat San Lorenzo (the reigning Libertadores champions) to win the Recopa Sudamericana, and eyes turned to the grandest prize of all: the Copa Libertadores. River’s 2015 Libertadores campaign became another fairy-tale. In the round of 16, fate paired them with Boca Juniors yet again – and once more River prevailed, in a notorious two-legged series that was cut short by a pepper-spray attack on River’s players at La Bombonera (CONMEBOL awarded the series to River). Having eliminated their biggest rival, River powered on to reach the final, where they faced Mexico’s Tigres UANL. On August 5, 2015, a packed Monumental watched River defeat Tigres 3-0, with goals from Lucas Alario, Carlos Sánchez, and Ramiro Funes Mori. The victory secured River Plate’s third Copa Libertadores title in club history. It also completed what one Guardian writer called “the most remarkable transformation in the team’s history,” coming just four years after the club’s relegation. Under Gallardo’s leadership, River had gone from second-division sorrow to standing atop South America. “The history of this club is about fighting for these kinds of competitions,” veteran midfielder Leonardo Ponzio said amid the celebrations. “Today is the greatest you can achieve as a club, and we did it.”t His words rang true – River’s long-held identity as a continental powerhouse had been emphatically reclaimed.

With the 2015 Libertadores crown, River qualified for the Club World Cup in Japan, where they reached the final (ultimately falling 0-3 to a Lionel Messi-led Barcelona). But setbacks like that did little to slow Gallardo’s River. If anything, they fueled the hunger for more. Over the next several years, River Plate systematically collected trophies, big and small, under the Gallardo regime. Domestically, the team snapped up three Copa Argentina titles (2016, 2017, 2019) and a Supercopa Argentina (2017 edition, won in early 2018) by beating Boca Juniors 2-0 in a highly charged one-off final. Internationally, River kept conquering: they added another Recopa Sudamericana in 2016 and yet another in 2019, and even claimed the minor Suruga Bank Championship in 2015 (defeating Gamba Osaka in Japan). By simultaneously holding the Sudamericana (2014), Recopa (2015), and Libertadores (2015), River became the first club ever to hold CONMEBOL’s three active international titles at once. Gallardo’s knack for knockout tournaments earned him the nickname “Napoleón” – a moniker reflecting his strategic genius and winning aura in decisive battles.

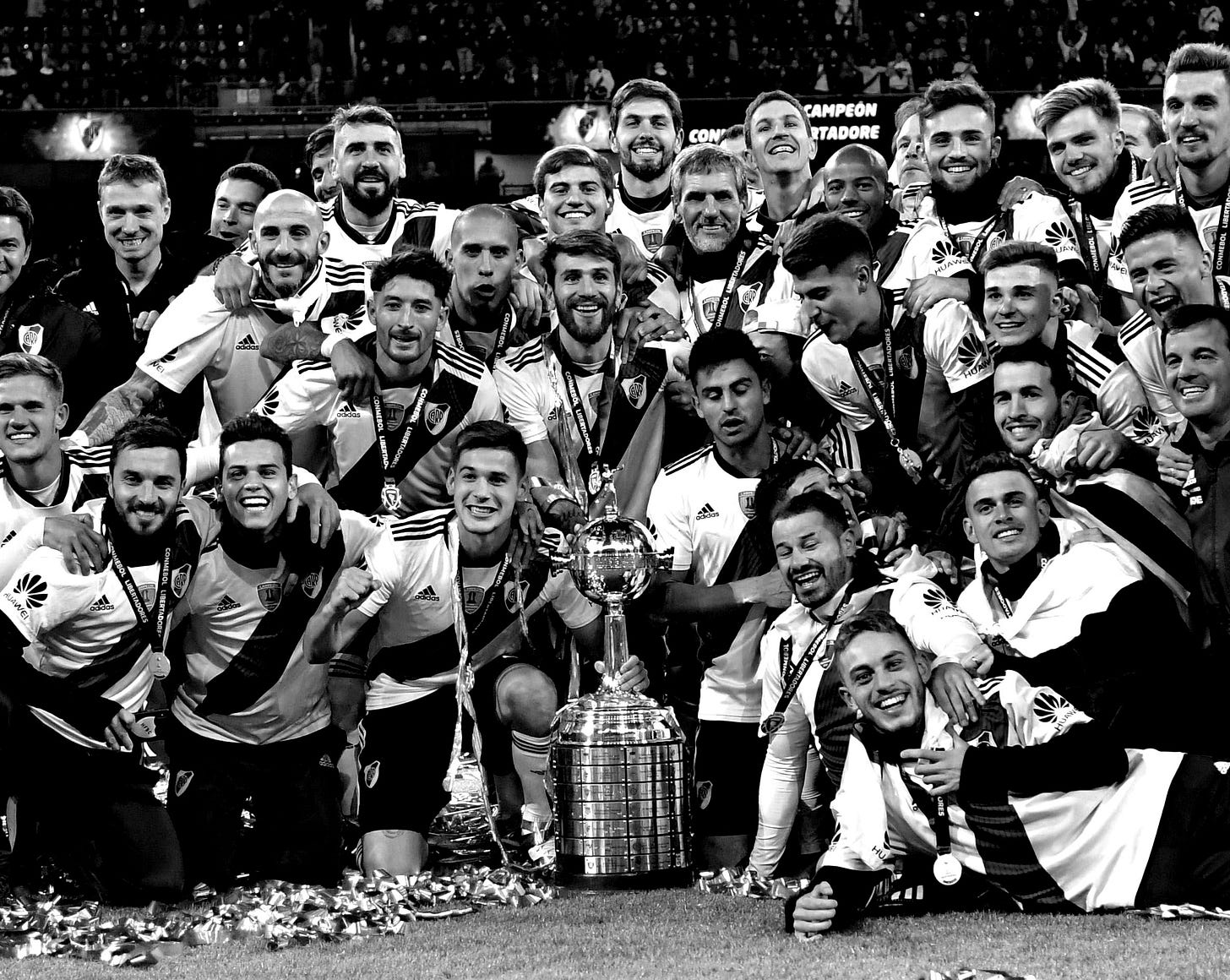

No battle, however, was bigger than the 2018 Copa Libertadores final, an epochal event that will be remembered for generations. In an unprecedented Superclásico final, River Plate faced Boca Juniors for the Libertadores title – the first time Argentina’s two giants met for the continent’s crown. The two-legged final became a saga: after a 2-2 draw in the first leg at Boca’s Bombonera, the second leg was marred by fan violence (Boca’s bus was attacked en route to River’s stadium). The match was controversially relocated to Madrid, Spain – neutral ground, 10,000 kilometers from Buenos Aires. On December 9, 2018, at the Estadio Santiago Bernabéu, River and Boca played out a final for the ages. Boca struck first, but River equalized in the second half through Lucas Pratto, forcing extra time. In the 109th minute of extra time, Colombian playmaker Juan Fernando Quintero – a super-sub with a magical left foot – scored a stunning long-range goal to put River ahead 2-1. And at the death, Pity Martínez added a breakaway goal to seal a 3-1 win (5-3 on aggregate). River Plate were Copa Libertadores champions once again – their fourth Libertadores title – and this one came at the expense of their fiercest rivals, on a stage and in circumstances no one could have imagined. It was the crowning achievement of the Gallardo era. “Nos da derecho a festejar para toda la vida,” Gallardo said of beating Boca in the final – “It gives us the right to celebrate for a lifetime.” Indeed, the triumph handed River eternal bragging rights in the rivalry. As Al Jazeera noted, it guaranteed “bragging rights over their neighbours for many years to come.” Striker Lucas Pratto, who had scored in both legs of the final, put it poignantly amid the celebrations: “We want to enjoy this because I don’t think we’ll win another Cup against Boca like this.” It was a once-in-a-lifetime moment – the “biggest joy in history,” as captain Leo Ponzio would later call – forged directly out of the club’s deepest pain seven years prior.

By the end of the decade, River Plate had firmly reestablished itself as Argentina’s preeminent club of the era. Under Gallardo’s command (2014–2021), River amassed 12 official titles (eventually 14 by 2022), making it the most fruitful period in the club’s history. These included multiple international championships – highlighted by two Copas Libertadores (2015, 2018) – and a sweep of national cups and supercups. The only trophy that eluded Gallardo for a while was the Argentine league title itself, but that too was rectified in 2021. In late 2021, River won the national league (the Primera División championship) in dominant fashion, securing the long-awaited first league laurel of the Gallardo era. Fittingly, that 2021 title was clinched on home soil with a rousing 4-0 win and was followed by a festive lap of honor for retiring captain Leonardo Ponzio – one of the few holdovers from the 2011 relegation team, now bowing out as the most decorated player in River’s history. It felt like the completion of a cycle: the club that had imploded a decade earlier had rebuilt and reached even greater heights than before.

A key feature of River’s resurgence was its dominance in head-to-head clashes with archrival Boca Juniors during the Gallardo years. Historically, Boca had often gotten the better of River in high-stakes encounters (especially in the 2000s). But from 2014 onward, the tide turned dramatically. Gallardo’s River defeated Boca in five consecutive knockout ties across various competitions: the Copa Sudamericana 2014 semifinal, the Libertadores last-16 in 2015, the aforementioned 2018 Libertadores final, the 2019 Libertadores semifinal, and also a Supercopa Argentina final in 2018 (2017 edition)r. Each victory further expunged the trauma of 2011, as if River were vanquishing every ghost and banishing any notion of inferiority. By 2021, River fans could delight in the irony that in the span of ten years, their club had gone from the humiliation of playing Belgrano for survival to beating Boca for the greatest title on the continent.

From Ashes to Glory: Ten Years On

As the decade closed, River Plate stood as a triumphant example of resurgence in sports – a case study in how an institution can rebuild from its lowest ebb to reach new summits. “Es 26 de junio de 2021. Diez años después de la oscuridad, River brilla más que nunca,” wrote La Nación: It is June 26, 2021 – ten years after the darkness, and River shines brighter than ever. That date marked a full decade since the relegation, and River was not just back on its feet; it was striding far ahead of the pack. In those ten years, River won multiple league titles and international championships, regained financial stability under President D’Onofrio’s management, and earned recognition as one of the top clubs in the world (finishing as high as #9 in the FIFA Club World Ranking of the 21st century). The club’s stadium, the Monumental, became a fortress of celebratory nights rather than a cauldron of despair. The supporters who had once rioted in anger were now routinely organizing victory parades and even broke a Guinness world record in 2012 by unfurling the longest football flag ever, in a jubilant display of River pride.

There is a saying in football that sometimes you must lose in order to win. In River Plate’s case, the loss was as drastic as it gets – dropping to the second division – but the club turned that into the catalyst for a comprehensive renewal. Enzo Francescoli reflected that the 2011 ordeal, painful as it was, forced everyone at River to rethink and refocus: “Sin dudas, cuando uno toca fondo, hay que empezar de cero… Volver a empezar pensando en lo que fue la historia de River.” (“Without a doubt, when you hit bottom, you have to start from scratch… to start again thinking about what the history of River was”). That history – of attacking flair, youth development, and sporting excellence – guided the rebuild. It is no coincidence that the resurgence was led by River icons (Almeyda, Ramón, Gallardo, Francescoli) who understood the club’s DNA. They combined old values with new methods, blending homegrown talents with shrewd signings. The likes of Jonatan Maidana and Leonardo Ponzio, who experienced the bitterness of 2011 firsthand, became the backbone of the golden generation that followed – their leadership forged in adversity. “Joni Maidana estuvo entonces y ahora es campeón de todo,” Ponzio noted – Maidana was there (in 2011) and now he’s champion of everything.

As for the River supporters, their journey from agony to ecstasy forged an unbreakable bond with the club. The terrace anthem “en las buenas y en las malas mucho más” was no longer just lyrics but lived experience. The fans had shown up in the bad times, and they were rewarded with historic good times. In the words of Leonardo Ponzio, “Las cosas pasan por algo para que después venga lo mejor.” (“Things happen for a reason, so that afterwards the best comes”). Few could argue that “the best” hadn’t indeed come: River’s worst moment gave birth to arguably its greatest era.

From the rubble of 2011, River Plate constructed a dynasty, one that by 2021 had won not only trophies but also the admiration of the football world for its style and resilience. The club’s tale is now recounted as a dramatic arc: a giant knocked down, rising stronger than ever. It’s a story of reckoning and redemption, of a fall from grace that became the springboard for glory. River’s motto “El Más Grande” – “The Greatest” – once seemed cruelly mocked by their collapse. Ten years on, it felt entirely apt again, burnished by the trials overcome. In June 2011 River Plate hit rock bottom; in the decade that followed, they turned that rock into the foundation of a new legacy. The fall of the Millonarios marked an end of an era – and the beginning of one. The phoenix had risen from the ashes, red sash and all, to reignite the fire in Núñez. River Plate was home, and River Plate was glorioso once more.